We're all just barnacles on the hull of late capitalism: A review of Virginie Despentes' 'Vernon Subutex, Volume 1'

If you want to know how your artsy, liberal best friend ended up voting for the extrême droite . . . read this novel.

VERNON SUBUTEX, VOLUME 1

French Edition: Grasset, 2015

English Edition: FSG Originals, 2019. Trans. by Frank Wynne

Niveau de français: Medium-Challenging

1.

"Putain, ça passe vite"—in the opening volume of Virginie Despentes' delightfully unhinged Vernon Subutex, time does a lot of things, but the one thing it does not do is go by fast. The opening scene, in which the title character is kicked out of his Parisian apartment, takes place over a single morning and afternoon, and runs 46 pages.1 The first 24 hours: 64 pages. The first 48: 95.

Outwardly, little happens. Vernon, who has been unemployed ever since his record shop, Revolver, folded six years prior, wakes up to the news that Alex Bleach, a French rock star, has died, drowned in a hotel bathtub in the middle of the afternoon. Bleach is the latest of Vernon's friends to join what the narrator calls his série noire. In flashback, Despentes runs through them rapidly, like a montage. Bertrand: throat cancer. Jean-No: car accident. Pedro: heart attack. To these, we can now add Alex, who also died of an overdose, one of two dignified exits available to those in his line of work. (The other, of course, being a plane crash, RIP Buddy Holly.) But the glory days are over, and the joke is typically bleak Despentes: Our modern-day rock stars can't even get their suicides right. "The hotel was too shitty to make anyone jealous," Vernon thinks, "but not shitty enough to be labeled exotic."

Like Alex's three close friends, Bleach is dead before the age of 50. Though only one character in Vernon Subutex could really be considered elderly, the specter of aging and death haunts the entire book. It is also the occasion for the reflection that opens this review:

Only when we get old do we understand that the expression, "shit, how time flies", is the one that summarizes most pertinently the spirit of the thing.2

For the translator, ça passe vite—literally, 'it passes fast'—is fairly simple. The problem is putain, an all-purpose French curse, just as useful for moments of astonishment as moments of reproval; it's similar to 'fuck', while not being quite as forceful. Stub your toe? Putain! See something cool? Putain! Get your bike snatched? Pu-TAIN! In every case, it's the intonation that conveys the meaning, which cannot really be reproduced in print. For me, putain is the most quintessentially Parisian curse, both light and efficace, and it remains just as popular now, during Emmanuel Macron's second term, as it was in 2012, during the beginning of François Hollande's first, when Vernon Subutex is set. Though that era may seem impossibly distant now, the novel's grasp of politics is distinctly contemporary. Despentes astutely captures the impending rightward shift of French politics, culminating in the RN's strong showing in this year's parliamentary elections, and the emergence of Marine Le Pen as perhaps the most powerful politician in France. Here, for instance, is Sylvie, one of Alex's ex-girlfriends, who has a son named Lancelot, one of many secondary characters Despentes sketches in great detail without granting them a presence in the main narrative:

Her son is right-wing. At first she thought it was just to piss her off, but finally she came to accept that clever young guys were no longer systematically on the left.

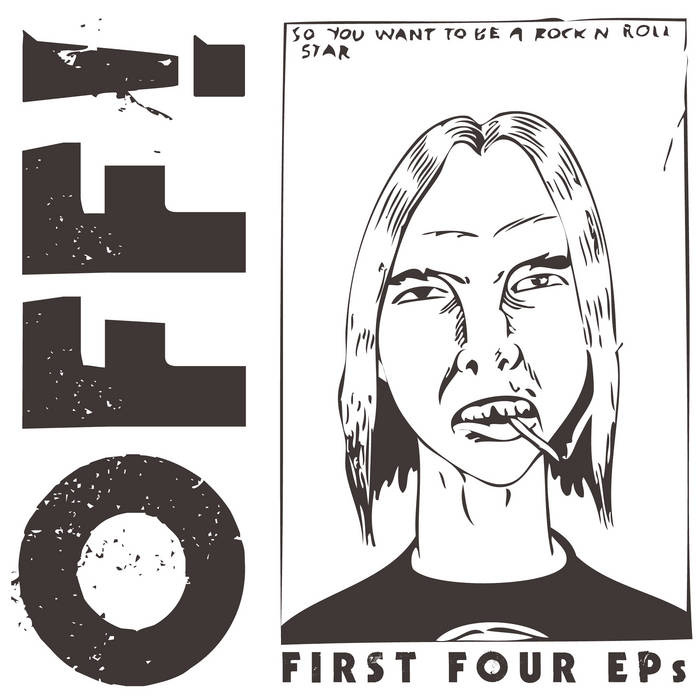

Strangely, however, for a book so focused on each character's personal politics, the references to the outside world are nearly all American: the grand success of The Artist at the Oscars, the shooting at Sandy Hook, the failure of the U.S. to stop the civil war in Syria, and, above all, the ubiquitous use of Facebook. The musical references, too, are mostly American, and almost exclusively Anglophone. For every mention of a French star like Johnny Hallyday, there's an inside joke about the hardcore band Minor Threat (did you know they were straightedge?) or the shitty solo albums put out by various members of The Strokes. Alex Bleach himself is unlikely—if he had really been the mash-up of D'Angelo and Iggy Pop the narrator so clearly wants him to be, he would have started writing his songs in English a long time ago, just like Phoenix.

These small contradictions hint at a larger one, which is nevertheless an essential part of what makes Vernon Subutex so incredibly cool to read in French. More than any other contemporary French writer I've encountered, Despentes' prose style depends for its effects on a deep knowledge of American culture and the English language. On a surface level, the novel is teeming with Anglicisms—open plan, un shooting, cash, le destroy, la lose, easy going, bodysnatché, des sunlights—which reflect the constant war that English is making on French, especially here in Paris. It's a war of occupation in which the French are both victims and, because so many of them speak English, collaborators. At a deeper level, the prose often relies on understanding the subtle differences between English and French homonyms, playing one against the other to achieve a comic effect that can't be reproduced in translation. After Vernon is kicked out of his apartment for failing to pay the rent, he crashes for the night with Emilie, a former Revolver regular who used to play bass in a purist punk band, and now lives a solitary bobo life, financially stable but emotionally stale:

Emilie est devenue balistique sur la propreté. Avant, elle s'en foutait royalement.

I prefer a fairly literal translation:

Emilie is now totally ballistic about her stuff. Before, she didn't give a royal fuck.

Frank Wynne opts for trying to reproduce the force and the slanginess of the original, without a direct equivalent of balistique or royalement:

Emilie has become fanatical about cleanliness. Time was, she didn't give a shit.

While I like 'time was', I think both devenue balistique and s'en foutait royalement call for stronger phrases that better reflect the uncompromising attitude of Emilie's younger punk self. While writing this line, Despentes was clearly thinking of 'go ballistic' and 'royal fuck-up' (possibly 'royally screwed'), which she then half-converts back to French in a wink to the reader who can simultaneously do the rough translation back into English, to catch the original sense. Some of these phrases, like s'en foutait royalement, you might actually hear on the streets of Paris, while others, like devenue balistique, seem to be coinages unique to the book. With this mixture, Despentes has found a stylistic corollary to the way that French is spoken in modern-day Paris. Though it was published nearly a decade ago, her prose captures precisely what it feels like to be here now.

2.

When I first moved to Paris a year ago, I assumed that the ubiquity of English in written materials—on signs, ads, menus, etc.—was just a sop to tourists. Yet the longer I've spent here, the more I've noticed that even written media clearly targeted at French people will often be written in English, or in some awful hybrid of the two. Here's my favorite recent example, from the French coffee brand Columbus Café: "45 MIN OF TRAJET IS UN PUR BONHEUR WHEN YOU COMMENT TE FAIRE PLAISIR." Clearly, this is meant for Parisians—what tourist, after all, suffers through a 45 minute trajet on the Metro? And it gets worse. What is this ad for? Le plus French des cafés latte, a phrase that manages to butcher three languages at once.

Despentes is also a butcher; the difference is that she knows how to wield a knife. Her French is often incredibly vulgar, but many of her best lines are deliberately fussy and formal. Take that line about the passage of time. Here it is in French:

C'est quand on devient vieux qu'on comprend que l'expression <<putain, ça passe vite>> est celle qui résume plus pertinemment l'esprit des opérations.

It's that last bit that isn't really translatable. L'esprit des opérations seems to gesture toward the English phrase 'the way things work' (Wynne opts for 'the workings of the process') while, in a higher register, est celle qui résume plus pertinemment plays well against the quick and vulgar putain, ça passe vite, while leading nicely into the final, offbeat phrase. Into the space created by the semantic ambiguity of l'esprit des opérations, la vie and la mort can momentarily coexist, reminding us that most proverbs about life are really about death.

Much of the humor in Vernon Subutex is found in the skillfully rendered contrast between these different registers, which is much wider than in most modern French prose. And while Despentes herself is generally seen as embodying a very specific kind of punk Parisian cool, her prose is anything but. In fact, she's a lot like Dickens, that most campy and uncool of writers, whose extraordinary creative energy, just like Despentes', often overwhelms his interest in keeping the story on track. Despentes wants her French to be more like English, which excels at mixing registers because it is itself a mongrel language, half-Germanic, half-Romantic, ready to hoover up words from nearly any conceivable source, and spit them back out in almost any conceivable order. Why English? Because English is the language of money and power. And however much the French welfare state might soften the lash of our foreign tongue, money and power, in Despentes' view, are what run modern Paris. When you read her in English, however, the effect disappears—not so much lost as whitewashed.

Here's an old joke: What do you call someone who speaks two languages? Bilingual. What do you call someone who only speaks one? American. Yet this joke misses the truth all American tourists instinctively understand, which is that they do speak two languages: English and money. The reason everyone listens to them speak the first is because they are fluent in the second. Despentes recognizes this, and that's why the texture of her novel feels so extraordinarily true to my experience here, even though the book itself does not contain a single non-French citizen, much less someone who is not a native French speaker. By excluding foreigners, the narrative may even be fighting a rearguard action against the encroaching gentrification of the prose itself. Though Despentes has written a great book that, at its core, is about one ordinary man's disturbingly ordinary descent into homelessness, she does it in a French that speaks, with impeccable fluency, the language of money. It is this central contradiction that animates the powerful first volume of Vernon Subutex, while also limiting the emotional impact and narrative interest of the rest of the series, which posits a fun, but ultimately unconvincing alternative to the grammar of capitalism that structures her initial approach.

3.

In the cultural economy of Vernon Subutex, however, it is not so much that Frenchness is being dominated by American-ness, as it is that the corporate gangsters who run the somewhat exploitative but cool American mass culture, like vinyl, are being systematically dismembered by the corporate gangsters who run incredibly exploitative and unrelentingly shitty American digital mass culture, like Facebook. Vernon's living, and his lifestyle, were premised on two things that no longer exist: a record store as a place to hang out, meet people, and kill time, and the record dealer as a small but essential part of the music industry ecosystem. Even when mining nostalgia for this lost way of life, though, Despentes is sharp and funny. On the cusp of Hurricane Napster, here's how she describes the hubris of the record industry:

Some claimed it was karmic, given how much of a killing the industry had made on CDs—resell all your clients the entirety of their discography, using a product that cost less to make and sold for twice as much at the record store . . . with nothing in it for real music lovers, who had never complained about vinyl.

The irony, though Despentes never mentions it, is that if Vernon had been able to hold out just a little longer, this sense of nostalgia for the analog era might itself have turned out to be profitable. Revolver died just before the beginning of the so-called 'vinyl revival', and Vernon might have been well-placed to serve as the old head for the next generation of boutique vinyl sellers. Vernon Subutex is, in large part, about the awkward but often effective means by which Gen Xers transition to the demands of the so-called gig economy. Some take advantage, finding gray areas in these new online markets to exploit. A butch lesbian called The Hyena—yes, that's her name—has made a specialty of what she calls the lynchage digitale. (Online, it's much easier, and more profitable, to destroy reputations than to build them.) Some withdraw, partially or permanently, in order to live on accumulated capital. Sylvie, for instance, kept the apartment in the divorce, receives alimony that's equivalent to two SMIC, the French minimum wage, and also skims a little off the top from her parent's rental properties. Xavier, a failed screenwriter, who admits to Vernon that, at the end of the year, he has difficulty making SMIC himself, has married rich. Interestingly, he is the one who points out one of the major contradictions of this new, supposedly innovative economy: It is absolutely filthy with feudalistic rentierism. Here is Xavier on his in-laws:

Her parents have never worked. Can you believe it? Rentier, it still exists. Papa watches over the family fortune, and maman helps out. Cheapskates just like all rich people, they count every penny. And then you hear them talk about smicards . . .I'm a liberal and pragmatic guy, you know me, I don't have any time for Bolshie fantasies. But you have to hear to believe it . . . He's never worked a day in his life, my father-in-law, but all the unemployed are shirkers who don't want to get their hands dirty. It's sincere—they're convinced that everything revolves around merit. Logically, those who have less, merit less. They think that if, tomorrow, they were out of work, with their nice, clean appearance and hard work ethic, they'd find a job right away, they think if they applied themselves and made themselves indispensable, they’d climb the ranks. The rich, they're still stuck on merit. It's incredible.

The truth, of which everyone is Vernon Subutex is aware, is that an ever-increasing number of people do an ever-increasing amount of work for almost nothing, while a small number, who have squatted in the right place, do almost nothing and soak up a great deal. The book is, essentially, about how each character adapts to this persistent and invasive illogic to which they are forced to submit. And even those, like Xavier, who do so with relative good humor are still, just underneath the surface, boiling with resentment. Papa and maman, after all, are content to be what they are, barnacles on the hull of late capitalism, and have no interest in climbing the ranks of a brutally competitive industry in rapid decline, wrecked by the same forces that felled the record industry. Where does all this resentment get channeled? Where it always does. Just a few pages before his incisive capitalist critique, Xavier is triggered after he flips on the news and finds himself watching commentary by the well-known journalist Elisabeth Levy:

But if you don't like France, pack your bags and go home, fatass. These Zionists drive me crazy, they're the only ones we ever hear from. We're in a Christian nation, aren't we? I've never been an anti-Semite, but if you want my opinion, I would light up the entire region with napalm, Palestine, Lebanon, Israel, Iraq, Iran, same shit: napalm. Over top, we'd build golf courses and racetracks for Formula 1. I'd take care of it real quick, you'd see...In the meantime, it gives me a headache to listen to some half-Arab Jew talk about France as if she was right at home.

The reference behind this tirade, which Xavier would likely know, is to Reagan's famous quip about Vietnam: "We could pave the whole country and put parking stripes on it and still be home by Christmas." Xavier's suspicion is that Elisabeth is using some nefarious combination her Arabness, her Jewness, and her womanness to cheat this illogic—you can measure the strength of the resentment he feels by the severity (and the creativity) of the punishment he proposes. At the same time, he is envious, searching for some part of his heritage that he can claim as his own. What is Xavier working on in his spare time? A biopic about Drieu de Rochelle, an avant-garde writer whose early and fervent support of the Fascist cause made him one of the most prominent pro-Nazi intellectuals during the Occupation. If you want to know how your artsy, liberal, and pragmatic best friend ended up voting RN (or Trump), this is it. In "Who Goes Nazi?", an essay originally published in Harper's Magazine in 1941, the journalist Dorothy Thompson anatomizes the different types of people who would, or would not, support fascism. Xavier is most like Mr. C, an 'embittered intellectual' who is, nevertheless, 'not a born Nazi':

He loathes everything that reminds him of his origins and his humiliations. He is bitterly anti-Semitic because the social insecurity of the Jews reminds him of his own psychological insecurity....He is the product of a democracy hypocritically preaching social equality and practicing a carelessly brutal snobbery. He is a sensitive, gifted man who has been humiliated into nihilism. He would laugh to see heads roll.

4.By now, you may have noticed that I have strayed very far from the original point, which concerned the way the novel handles time. See what I just did there? This is exactly how Despentes keeps her extraordinarily long and largely static scenes moving: Flashback nested inside cultural observation nested inside politically incorrect opinion nestled inside another flashback, and so on, until the narrator has been gone for so long from the original scene itself that she has to remind the reader of where we are, and what the hell, exactly, is going on. If the presiding drug of Vernon Subutex is cocaine, which nearly everyone in the book does, at one point or another, then the presiding narrative spirit is that of a stereotypical cokehead, whose irrepressible energy has to compensate for a lack of structure, and a certain weakness for repetition and circular logic.

Examples, on en a plein. Laurent Dopalet is a film producer, meeting a director named Audrey for the French equivalent of a power lunch. (Le power lunch is not in Vernon Subutex, although it should be.) Audrey takes a seat on the banquette, but she hasn't even opened the menu before Laurent begins analyzing her top to bottom, the male gaze in hi-def. "She could have made an effort," he thinks:

She's not even wearing makeup. A bulky sweater, with a high neckline, run-of-the-mill sneakers, her roots are a dull white, she hasn't made a trip to the hairdresser in months. She hardly manages a smile. She's sleeping with Bertrand Durot and no one in Paris wants to piss off the head of France Télévisions. Laurent couldn't reasonably refuse this meeting. He will not produce her film. So much crap comes his way. What is he supposed to do in the middle of this shitstorm? The thing won't sell thirty tickets. It's the newest obsession of female directors—the stories of postmenopausal women, who smoke cigarettes while talking with fuckups.

Does Audrey really look this drab? I doubt it. Beyond the fact that anyone interested in advancing their film career, i.e., literally everyone in film, would almost certainly come to such a meeting wearing something sharp, does it seem likely that the lover of a powerful television executive would go for months with visible roots? What seems more likely is that Laurent, and possibly Despentes, has confused Audrey for a character in Audrey's proposed film.

In many places, Despentes starts with an American cliché—the Weinstein-esque film producer, the coked-out investment banker, the desperate housewife—and then scrambles like mad to paint them as individual characters with, evidemment, the requisite French accents. At the start of each successive chapter, which usually takes place from a new point of view, it often feels as if the narrator is working out who each character is in real time. While this can be thrilling, it also requires layers of backstory that may be shoved in more for the writer's sake than the reader's. A few paragraphs later, Laurent has the following extremely convenient thought:

But it wasn't the the female director's presence that was making him feel ill. He needed to go over what had happened that day, then the day before, to situate precisely the moment where it all began.

It's four more pages before poor Audrey is mentioned again, briefly, then another four before she finally says:

"Are you still listening to me?"

"Yes, yes, sorry . . . I was upset, these last few days, since the death of Alex Bleach . . ."

"You were close?"

"We were. We hadn't seen each other in a long time, and his disappearance really tore me up. But do go on. I'm listening, continue."

A few sentences later, however, Laurent compares her to a bulldozer, "enclosed within the noise she produces, obsessed by her objective." The irony is that this is a rather perfect description of Laurent, and also of Vernon Subutex, whose story is powerful but also extremely slow. How can we reconcile the speed of the reading experience with the discursiveness of the narrative? To extend the metaphor, the novel is like that first, perfect coke high, the prose itself like fishscale cut with just the right amount of downers. So how does Despentes achieve some of the immense pathos found in the best passages of the book? By bulldozing her way through backstory and cliché until she finds a moving or interesting thought. Here's Laurent on power:

You might think it's sitting in your office, giving orders, never being contradicted. You might think it's easy. On the contrary—the closer we get to the summit, the harder we have to fight. The higher we climb, the costlier the concessions become . . . . at the top, we know nothing except the fear of being stabbed in the back, the rage of betrayal, and the poison of false promises.

Throughout the series, Laurent Dopalet remains a cliché of a film producer, but in the first volume he is the most fascinating and dynamic version of what he represents as a typical member of his class. He is less a character than one of the many faces of capitalism, personified. The reason this works is that we are all, to some degree, living underneath the masks of a role we've constructed for ourselves, in order to be acceptable to the market. Live underneath the mask long enough, Dopalet might argue, and you become it. What Despentes captures extremely well is that no one, even the homeless, is exempt from this endless demand for endless roleplaying. Late in the novel, when Vernon has finally run out of couches to surf, he ends up on the street, where he meets an SDF (sans domicile fixe) who gives him some tips for survival:

If you really need money, for example to get a hotel, make sure you're standing up, don't sit, and make sure to smile when you beg, if you find a little joke to make don't hesitate, the people you're begging from have shitty lives, don't forget that, if you make them smile they'll put their hands in their pockets...they love the idea of the poor asshole who keeps his spirits up.

5.

A brief biographical sketch of Virginie Despentes, who was born Virginie Daget in Nancy in 1969. Her parents were postal workers who were heavily involved in their local union; one article I read claimed that, at a demonstration, a two-year-old Virginie raised a tiny fist during the Internationale, a story more notable for its mythic aspect than its verisimilitude. As a teenager, she spent time at psychiatric hospital, and later worked as a prostitute, a maid, and a clerk at an independent record store. (According to a friend of mine, 'Despentes' is the name of the street where she turned tricks, but I've seen multiple claims as to the precise origin of her nom de plume.) Her first novel, Baise Moi (literally, 'Fuck Me'), a rape-revenge fantasy, was published in when she was just 23. A series of novels quickly followed, most of which she claims to have written under the influence of drugs. ("I wrote my novel Les Jolies Choses in three or four days while I was on coke, it really unblocks you," she once said in an interview, sounding just like a character in a Virginie Despentes novel.)

In the late nineties, when she adapted and directed Baise Moi as a film, Despentes cast real porn stars and showed them having real sex. The film was subsequently banned in France, which, let me tell you, is no mean feat. Her overarching interest is in the destructive capacity of violence, especially sexual violence, and how it alters the self-conception of those affected by it. As a polemicist, she is firmly on the side of those who suffer from violence, especially women. Creatively, however, she is as fascinated by the person who commits violence as she is by the person who has been violated. She is, in other words, fascinated by men, especially those capable of violence. In an interview on La Grande Librarie, a well-known literary TV show, Despentes was asked by the host, Augustin Trapenard, a real smoothie, how she manages to canaliser—channel—her own anger and penchant for violence into her work. She hems and haws for a moment, then turns the question back toward Trapenard:

For me, the guys who talk about the channeling of violence are the guys who aren't violent.

You can't understand violence by talking about it. Indeed, those who talk about it most probably understand it least. For Despentes, violence is profoundly linked to class, a form of expression available to those who can't make a living through expression alone. Take Patrice, a former member of the Nazi Whores—in English, natch—the knives-out punk band in which Alex Bleach first made his name. When we meet Patrice, he has a runny nose and diarrhea, and the narrative colonoscopy Despentes administers only gets more painful from there. Patrice is bitter, but not intellectual; nostalgic for the analog era but clear-eyed about his limits as an artist:

One night during rehearsal, while going down to the basement, he realized that it just wasn't doing it for him anymore. He wanted to park himself in front of the tube on Saturday nights, get a decent job without needing to make sure that he could be free Friday nights to play a gig in Bourg-en-Bresse. He went to tell the others. That's it, you're going to have to replace me. It was Alex who was the most hurt. But this just confirmed what he already knew—he wasn't living the same story as the rest of them. Alex didn't have a choice. No family, no job, no other ambitions. And he was the only one who had an ear, an idea of how to write a hit.

Patrice, who lives alone and works for La Poste as a deliveryman, is enormous, tattooed, "a Marxist Hell's Angel who quit the Angels." His ex-wife, Céline, left him years ago, along with their two kids. In his late forties, he is still easily capable of inspiring physical fear; for many years, the main target of his violence was his wife. As always, Despentes is attentive to the interplay between role and act:

It was complicated, the relationship between him and Cecile. It wasn't just 'a violent guy hits a pregnant woman'. It's more complex. He loved her like crazy, he treated her like a princess. But he also lost his temper from time to time.

Violence itself is a channel:

Just after the anger, he felt emptied. He watched his wife cowering in a corner, he wanted to erase what had come to pass, help her back up and go for a walk in the sunlight, taking their sweet time, as if nothing had happened.

In her interview on La Grande Librarie, Despentes makes a distinction between merely talking about violence and what she calls l'acte of writing itself:

A priori, the idea we have of violence is that it passes to the act. What interests me, in my case, is to pass to the act, and write about violence.

I've always been skeptical of the idea that writing can be violent. The power of a work of art and the power of even a single blow are two fundamentally different things. So what does she mean by passer à l'acte? For Despentes, I believe, writing is not a compensatory act of violence, but an assertion, or reassertion, of control. This, as Patrice makes clear, is one of the main purposes of violence:

If the girl resists, if she's not scared right away, if she doesn't submit immediately, it can go further. You have to strike terror, she has to cower. Completely.

To inhabit these characters, especially the scumbags, the narrator doesn't try to reduce them, or even to critique them—instead, she controls them. The authorial voice surrounds them, inhabits them, follows them everywhere, she's privy to every single circumstance of their existence, even the most pitiful, they can't even take a piss without her knowing every thought that rolls through their heads:

Patrice couldn't believe it when he found out she had gone to a shelter for battered women. Even so, that's not what their relationship was, some cliché of domestic violence. But then, in fact, yes. It was the same old story. He is a caricature.

The contrast between Patrice and Xavier is interesting, and Despentes underlines it clearly. While Xavier, the embittered intellectual, would never hit his wife, it is Patrice who would never go Nazi:

Tomorrow, if there were barricades to man, a civil war against the profiteers, he would be seen as one of the heroes. He was getting old, his strength was waning. But he still had a bit left in the tank. He would love to see the blood flow. The bankers, the CEOs, the rentiers, the politicians...shit, guys like him, in times of war: heroes. He's sure that if he had something to fight for, he would never raise his hand against a woman again. As a soldier's wife, Cécile would have been incredible. There are few things tougher than a woman with a good head on her shoulders.

6.

One thing I forgot to mention: Despentes lives just a stone's throw from chez moi. In fact, I'm writing this review at a café in the 19th Arrondissement, maybe a 15-minute walk from La Butte Bergeyre, a kind of bobo eyrie of cobblestone streets and ramshackle single-family homes, from which Despentes apparently descends quite regularly, in order to walk her two dogs (presumably fierce, but who knows) around Buttes-Chaumont. Just like the enormous cliffs of Belvedere Island, around which author takes her daily constitutionals, La Butte Bergeyre is built on gypsum from an old quarry, which provides a beautiful but unstable foundation that limits the size of the homes, giving this micro-quartier the feeling of a pétit village, nestled high in the hills. Looking west, there is a beautiful view of Montmartre and the Sacré-Cœur; on summer evenings, it is not uncommon to find a few dozen people at the far end of Rue Rémy de Courmont, drinking bottles of soixante-quatre and enjoying the sunset. With few skyscrapers and a relatively flat topography, there aren't that many places within Paris to take the measure of the city as a whole; this is one of them, and maybe the best.

It's also the setting of the final scene of Vernon Subutex. For all of the extraordinary detail that Despentes lavishes on her characters, Vernon remains a bit of a cipher. Though the record shop is gone, throughout the novel he remains in his symbolic role a record dealer, standing behind the comptoir at which everyone bends an elbow, at one point or another, to unleash stemwinding monologues of such length and density that they often seem to take place outside time. On the rare occasions Vernon does speak in dialogue, the results are flat and often contradictory; Despentes doesn't seem as comfortable handling a character who's most common reaction is a shrug, and despite his long history as a lothario his easy success with women never convinces. In the beginning of the novel, his decrepit bachelorhood is itemized with surgical precision:

Right now, Vernon fucks less than a married man. He wouldn't have imagined he could go so long without sex. Facebook or Meetic are useful for picking up chicks, but unless we really go in for Second Life, eventually we have to go outside to meet the girl. Finding clothes that can pass for vintage as opposed to something an old bum might wear, finding some way to avoid cafés, cinemas, and above restaurants . . . as well as avoiding bringing them back to his place, so that they won't see the empty cupboards, the bare fridge, the disgusting mess—nothing in common with the sympathetic chaos of a guy who's always been single. At his place, there was an odor of smelly socks, the typical perfume of the man-child.

Just a few days later—though, very importantly, after around a third of the book has passed—he's sleeping with Sylvie, our desperate housewife archetype, who falls immediately and desperately in love with him. Honestly, as a scenario it's impossible to imagine, and Despentes can manage only a halfhearted attempt to square the circle: Sylvie thinks that if Vernon would just get his teeth cleaned, then he'd be presentable to all her rich girlfriends. As if!

What seems more likely is that Despentes has some kind of affection that she carries for Vernon, and Vernon alone, which makes him immune, to a certain degree, from the market-based logic to which the rest of the cast has to submit. This immunity has a cost, which is that, as a character, he never comes into focus. Even the people promoting the book seem to have no idea who he is. Here's the text on the back jacket:

Who is Vernon Subutext?

An urban legend.

A fallen angel.

The keeper of a secret.

The last witness of a changing world.

The final face of our human comedy.

Our collective phantom.

Really, he's just a broke dude who used to sell records. My cynical side says that Despentes has made the classic dealer's mistake: She's gotten high on her own supply. Xavier imagines being a feminist Arab-Jew as a kind of golden ticket into the kingdom of high snobiety—does Despentes imagine that the same pass is doled out to all mediocre white men? Yet in every other instance, Despentes knows better. Indeed, if there is anything that unites the characters in Vernon Subutex, it is their mediocrity. Not a single one of them is a whit more noble, brave, open-minded, gracious or intelligent than they would be in real life. The more I've dug into the book, the more I think that Vernon serves several functions in the book, that he is the one character that is more than a character, that he is the key that unlocked all the other doors for Despentes as a writer on this particular project. In a way, she owes him. He's the holy fool, the moral center of the series itself, without which it would still be sharp, but brittle and possibly stale. To give the thing its beating heart, Despentes had to grant this guy his peccadilloes, I guess, letting him hop from bed to bed like he was Alex Bleach in the flesh. Perhaps it was a small price to pay.

I often read novels that I know must have been hell to write, but still leave me unmoved. The author might have an extraordinary and personally profound reason for tackling a project, but the book itself can still lack a raison d'être. I'm not an expert on Virginie Despentes, and I'm hardly what you would call a superfan, but what is absolutely clear throughout the reading of this book is that it had to exist. While you're reading it, in fact, it feels as if it still exists, as if it always existed, that somewhere in the universe the world of the book is running along, perpetually at full tilt, coming at you with terrible speed. For the three weeks I was rereading the book and taking notes and writing this review, my Paris was swallowed by Despentes', my world by hers, bones and all. When I'm out having a beer at Point Éphémère on a beautiful fall evening, and a friend tells me about the refugee encampments that used to stretch along the banks of the canal after the Arab Spring, and the people who died there, when I go for a picnic at Buttes-Chaumont, and scan the abandoned railroad tracks, searching amongst the tents for signs of life, when I take in a sunset at the top of La Butte Bergeyre, on the same bench where Vernon ends up in the final pages of Volume One, with that peerless view looking high over Paris, all the way out to Montmartre, I know that I am just another decaying sack of blood and guts within the vibrant, beautiful, hostile, vicious, and teeming world that Virginie Despentes has created. I may know where she lives, but that means nothing, because she knows everything about me. While reading Vernon Subutex, I have the impression that she's not an author at all—she's a witch, a prophet, a force of nature; she's the wolf at the door, a laugh in the dark, the palm at the end of the mind. Wherever I go, she is watching.

All page references are to the French edition.

Please note that, unless stated otherwise, all translations are my own. Corrections welcome—nay, encouraged: pariscityoflit@gmail.com.