This is an English translation of a presentation I originally gave in French. I have to say that translating your own work back into your native language is extremely strange—almost like hearing a recording of yourself and trying to figure out if that is, indeed, the sound of your voice. (I don’t much like the sound of my own voice, which may explain why I don’t much care for this translation.) To give some necessary context: Georges Perec was a French novelist who helped found an experimental literary movement called OuLiPO in the 1960s. He did so along with a group of French writers and mathematicians who were looking for innovative ways to ‘systematize’ creativity. The title of this post is a reference to his book Les Choses: Une histoire des années-soixante, which in English was titled Things: A Story of the Sixties. Perec was famous for his literary experiments, including writing a novel without the letter ‘e’, as well as using direct quotes from other writers to create new stories. (Is it plagiarism if you admit it? If you truly create something new? Great question—I hope to get to this at some point.) Anyway, here is the text of the presentation.

First thing: Last week, I went to Chez Gibert—like a true Parisian, of course—to pick up a book by Georges Perec. On the second floor, in the section devoted to French literature, tucked away between Je me souviens (I Remember) and La vie mode d'emploi (Life: A User's Manual), I came across a small volume entitled Les Mots croisés (Crosswords). Naturally, I had the impression that this volume was some kind of wordplay. Given that Georges Perec is the author of La disparition (The Disappearance), a novel entirely without the letter ‘e’, I imagined words literally crossed, or struck, against each other, a bit like pinball, a game that was very popular at the time. In any case, that's not true. Les Mots croisés are just simply . . . the crossword puzzles that Perec did for the weekly Le Point for many years.

Second Thing: For those who want to check my math, there are five ‘e’s in the title of this presentation, and dozens in the first passage alone. (I’m not going to make an exact count, but safe to say there a lot.) Anyway, the point is that I have no clue how anyone could maintain this over three lines, much less 300 pages.

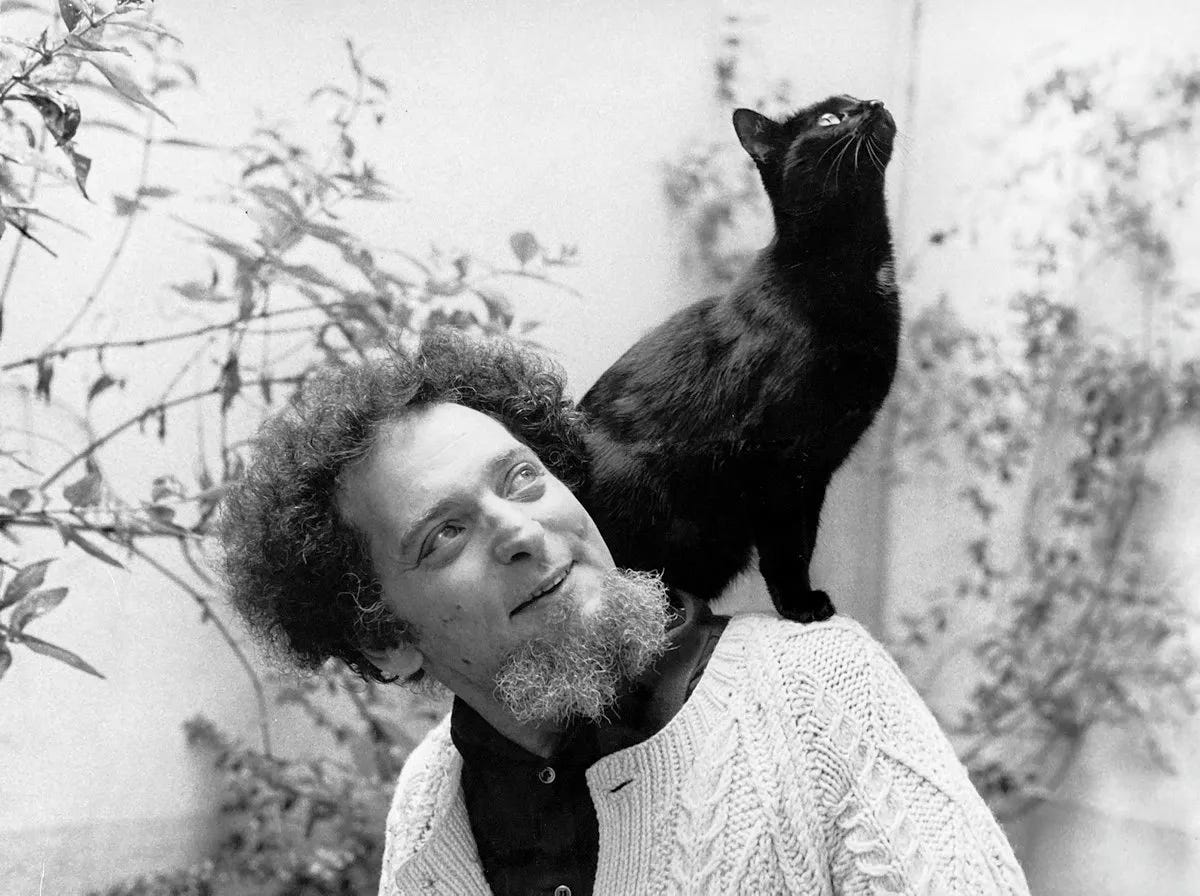

Third thing: In 1936, Perec was born in Belleville, the son of Polish Jews. At the outbreak of World War II, his father, Idek Judko Perec, who fought for the French Foreign Legion, was killed in action in June 1940, during the German invasion. His mother, Cyrla Sulewicz, remained in Paris until 1943, when she was arrested by French authorities and deported to Auschwitz, where she was murdered. During the war, the young Georges Perec was smuggled out of Paris by the Red Cross, then baptized to disguise his Jewish origins.

Fourth thing: In his memoir, W or the Memory of Childhood, Perec wrote, “I have no childhood memories.”

Fifth thing: After the end of the war, Perec grew up in a petit bourgeois family, the Bienenfelds. He attended a provincial boarding school, the Collège Geoffroy-Saint-Hilaire, and then did his military service. A very gifted student, he was not, however, very fascinated by the world of academia or the life of a professor.

Sixth thing: Who is this famous Saint Hilaire? I was curious. According to the website of the Catholic Church in France, “Saint Hilaire of Poitiers was a bishop and Doctor of the Church. Born into a noble and wealthy family in Aquitaine, this young man was gifted for studies, but the question of the meaning of life tormented him. ‘Where is happiness for man? What is the point of existing if one is to die? Is there a god?’” In my opinion, it's quite possible to see a connection between the young Perec and the saint for which the school is named.

Seventh thing: Of course, like the main characters in Things, Jérôme and Sylvie, the real Perec lived in a 35m2 apartment with his wife Pauline Pétras, whom he married in 1960. Right after their marriage, Pauline was accepted a post as a teacher at an international school, and they spent a year in Sfax, Tunisia. I don’t really know why I included this fact. I think it’s because I love the word Sfax. I’d also love to visit Tunisia.

Eighth thing: Here's an excerpt from an interview Georges Perec did with the TV anchor Pierre Desgraupes, who sounds like a TV anchor in a Perec novel. “We live in a consumer society,” Perec said to Desgraupes. “I studied motivation, I did a bit of sociology, I was in the field, I interviewed people, asking them what they thought of life, what they thought of their mattresses, their shoes, their washing machines.”

Ninth thing: In Life: A User’s Manual, his great 1978 novel, the main character is an eccentric millionaire named Bartlebooth, a tribute to Bartleby, Melville's famous “scrivener” who “preferred not to.” However, one could say that Bartlebooth “does want to.” For ten years, Bartlebooth studies the art of watercolor; for twenty years, he travels to the four corners of the globe, where he will make 500 watercolors of seascapes, all in an identical format; after they are finished, he will glue each one onto a wooden board and transform it into a jigsaw puzzle; finally, he will assemble each puzzle himself, until the end of his days. It is a project at once arbitrary and assiduous, rather like Perec's books, and perhaps, like life itself.

Tenth thing: Perec's obsession with puzzles is all-consuming. “I don't think,” he once said. “Rather, I search for my words.” When I read this quote, I thought of DeepSeek, the Chinese AI model that recently revolutionized the industry. Basically, the model doesn't “write”. In a given sentence, it instead makes predictions about the words that are always missing. As you've probably already guessed, it is indeed like a giant crossword puzzle.

Last thing: Bartlebooth's apartment is even more detailed than Jérôme and Sylvie's. The entire space is divided by the author into a 10-by-10 grid. Each square within the grid represents a fixed location: a staircase, a bedroom, or a hallway. Except for the hundredth square, which is empty. When I read an article about the intelligence that “generated” Life: A User's Manual, I thought it might well be that the hundredth square contained his childhood memory, the memory that Perec was always missing. And with that, our epic ends. Merci beaucoup.

Now that it's over, I must credit the writer Geoffrey O'Brien, who wrote an excellent review of a Perec biography in The New York Review of Books. In an Oulipo-esque twist, I admit that, here and there, I occasionally used near-direct quotes from the article. (Though by now it’s quite difficult to tell, as I had to re-translate the quotes back into English.)

witty and lots of personal style. fantastic